INTRODUCTION

In practical terms and at the most basic level, perspective is the technique of drawing, rendering, and painting on a flat surface in such a manner as to convey a projection of reality as it might appear to the naked eye: A simulation of depth and distance, commonly know as foreshortening. Please note I said “eye” and not “eyes.” I also said “simulation” instead of “duplication.” Indeed, for all its might and power and countless locks of hair pulled and cries of lament wailed in its honor by artists, illustrators, renderers, industrial designers, and architects, perspective has an Achilles’ heel—several of them, as a matter of fact.

The first and often overlooked limitation inherent in perspective is that it can only represent what one human eye (or camera lens) might see. On the other had, humans need two (healthy) eyes in order to grasp the holy grail of perspective representation: duplicating true three-dimensional space.

This is known as stereoscopic (the word “stereo” from Greek means “relates to space”) perception which can only be achieved through both eyes working correctly.

Therefore, in order for perspective representation to duplicate reality, it would have to duplicate the stereoscopic effect of our two eyes that project two slightly offset pictures onto our retinas, where they are in turn (magically) processed by the brain into what might be considered a benchmark for true representation of three-dimensional (3-D) space—which must be “felt” or “grasped” as well as “seen” for it to be worthy or being called “reality.”

For the majority of us, we live in a three-dimensional universe where our eyes provide us with the necessary feedback in order to perceive space correctly and navigate through it without bumps and bruises—and even with two healthy eyes, that’s not always a

guarantee!

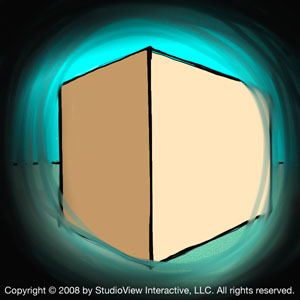

In other words, perspective representation cannot (in our known Universe) duplicate that which only two eyes can see and “feel.” Hence, perspective representation can only simulate what only one eye will see.

And unlike the real eye which is constantly moving, the “virtual” eye that will be the generator of our clever simulation (or illusion) does not move around. That means it has a rather limited field of vision.

To appreciate this simply look straight ahead with and cover one eye, and try not move your eyes and wait a few seconds. Soon enough, and if you can hold the eyes steady, you’ll begin to notice a constriction of the visual field resulting in loss of peripheral vision—tunnel vision. In addition, by so doing, you have lost your

inherent ability to experience “3-D” made possible only through the stereoscopic effect.

On top of all this we must come to grips with the fact that perspective presentation depends on the participation of the observer: the degree of success of the illusion is directly proportional to the observer’s own experiences.

Imagine a person born and raised in a place where there are no roads and telephone poles, no doors, no walls.

Now, imagine this person stumbles upon a photograph of telephone poles fading into a point on the horizon. While that person may appreciate the nature of the composition of the photograph, chances are he or she will have no clue that the smaller “stick” is actually the same size as the “bigger” stick just “ahead” of it.

Let’s push this example further: Imagine a person is born visually challenged and that eventually, and by some miracle of medicine, that person can see!

Now, that person looking down a street from a rooftop (for the first time) might reach down in an attempt to grasp the moving vehicles rolling a few hundred feet away from him or her. In other words, stereoscopy is great, but we still need experience in order to convert the data our eyes are giving us. In fact, a

person who was just granted the ability to see with both eyes has practically zero ability to “navigate” three dimensional space. Whereas, a person who lost vision in one eye — and despite the lack of stereoscopic effect— can still drive, and lead an normal life.

Experience is therefore key for It provides meaning. Furthermore, imagine how the evolution of photography and cinematography has influenced the way we readily accept exaggerated or dramatic foreshortened effects.

Can you imagine showing such images to an individual living during the Renaissance?

“The hand is many times the size of the head!” he or she might say.

Or how about if you showed that person a photograph of a building with a special lens designed to accentuate the effect of whais commonly referred to as “three point perspective”?

“My Lord, the walls are all leaning inward! These buildings are not even straight!” they might exclaim!

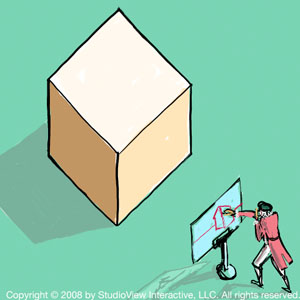

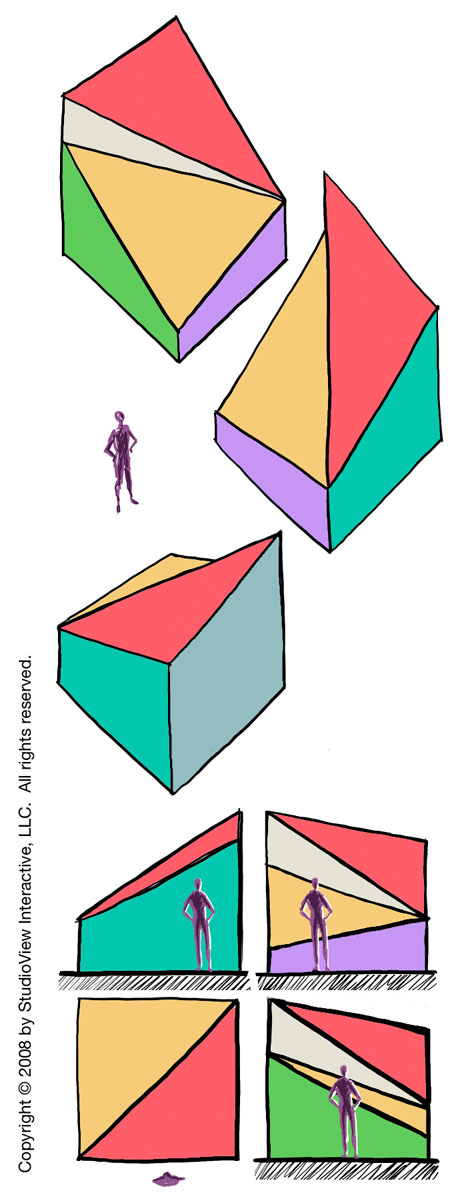

Compare that with our rather contemporary sophisticated visual palette where, not only are we not shocked by dramatic perspective featuring extremely foreshortened elements, we even expect it to be! We use such terms as “dynamic” versus “static” when referring to such images. And even when we see a rendition of something that looks nothing like a cube, we know it is a cube. But how do we know, believe, and trust that it is a cube? What sort of theory can we rely upon in order to deconstruct the journey from intuitive cognition to holistic expression? How do we learn to process and convert a mere two dimensional representation into an illusion of reality?

For starters, we need to establish a simple and practical theory of light propagation married with the technique of representing 3 dimensional reality by projecting it onto 2 dimensional surfaces, without foreshortening, thus preserving absolute dimension — a representation that only the analytical side of our brain can understand. In addition, we will also rely on our observation. Therefore, learning to draw what we see, no more, no less. These techniques are perhaps mutually exclusive. However, together, they will feed the subconscious and the result is phenomenal: you will draw perspective with a clear mind and in ways that no computer program could!

Yes, given hours, days, and perhaps months, a computer will generate a rendered perspective view.

But wouldn’t it be great to feel that we humans can still do what no computer can do? In fact, even today, no computer-generated perspective can be created without a vision that comes from within a human being. And for all its power, the computer still relies on humans to create these fantastic worlds we see on the screen. And when these worlds are created on conceptual drawings (and sculpture) created by individuals who have a true intuitive grasp of how to simulate 3 dimensional space and objects, using a language that people of their culture can appreciate, our culture as a whole benefits because of the fact that no two human beings can duplicate exactly their own work, let alone each others’. Human and technology working together can create wonderful things. The inherent uniqueness in each person’s work is key to combat the slow and insidious enemy: entropy — the degradation of the matter and energy in the universe to an ultimate state of inert uniformity.

Applied to visual expression this means, quite literally, a loss of identity.

Mario Henri Chakkour, AIA

"LIVING SKETCHBOOK™" Copyright © 2008 by StudioView Interactive, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Proceed to the Chapter One ----->